|

www.HealthyHearing.com |

Hyperacusis: Noise sensitivity that's painfulFor some people, the world is almost always too loud

Contributed by Joyce Cohen Key points:

A cat’s meow sounds like a lion’s roar. A turning page sounds like the crack of thunder. A toilet’s flush sounds like Niagara Falls. And a ringing phone, a singing bird, a beeping microwave—all feel like a knife stabbing the eardrum. That’s hyperacusis, a type of sound sensitivity disorder. In many ways, hyperacusis is the opposite of hearing loss. Instead of the volume of the world turned down, it’s turned up—sometimes to the point of pain. Loudness and pain define life with hyperacusis

Hyperacusis comes in a gradient of severity. Even mild cases, where sounds are perceived as abnormally loud, is debilitating. High pitches and low throbs tend to be the toughest to tolerate. How common is it?Unfortunately, there isn't much research about hyperacusis, including statistics on how many people have it. Estimates range from .002% of the population to a full 17%, though the latter figure applies more to people who feel discomfort from loud noise. In severe cases, people feel ear pain from even moderate noise. What causes hyperacusis?Excessive noise is a leading cause of hyperacusis, though science has yet to learn the mechanisms that lead to such auditory discomfort and pain. Hyperacusis is often the result of a noise injury, sometimes called acoustic trauma. This noise can be a sudden impulse noise, like an airbag explosion, gunshot or smoke alarm. Some people may have a tiny hole in their inner ear, known as third mobile window syndrome or superior semicircular canal dehiscence. Noise damage is cumulative, so hyperacusis can also come from less-loud but prolonged or episodic noise exposure—for example, too many concerts or too much listening with headphones or earbuds. Farming, manufacturing, construction and other such loud occupations are damaging to ears, as is military service. And there is growing recognition of the dangers of recreational noise, from activities usually considered healthy or enjoyable — gym class, concerts, sporting events. A head or neck injury is another cause of hyperacusis. In rare cases, the starting point is a sudden jerking movement on a roller coaster or similar movement. Drug side effectsSeveral medications are known ototoxins and can cause assorted ear problems, including hyperacusis. These include aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, loop diuretics, statins and some cancer drugs. Hyperacusis sometimes goes along with certain conditions or diseases, such as autism and Lyme disease. Pain hyperacusisThe more severe form—pain hyperacusis, sometimes called noxacusis or auditory nociception—is a new diagnosis in the field. It has been recognized only in the last 10 years, largely through the efforts of the late Bryan Pollard, who founded the nonprofit Hyperacusis Research and coined the term “noise-induced pain.” “Pain has long been underrepresented—and often, completely overlooked—as a component of hyperacusis,” he wrote. The pain often worsens with ordinary noise exposure. In extremely severe cases, people feel ear pain even in silence. When hearing is actively painful, “pursuing a normal life is impossible,” Pollard noted. “There is no place on earth without sound.” A trip to the grocery store, with its beeping scanners, squeaky carts and throbbing refrigerators, is painful. So is cooking a meal, in a kitchen where metal pots and pans can collide. Noise damage takes many forms

with ringing in the ears. Too much noise, building up over time, is why so many elderly people have hearing loss, which is the typical consequence of noise damage—and which is measurable, unlike hyperacusis and tinnitus. It remains a mystery why the same noise dose can cause hearing loss or tinnitus in some people, and hyperacusis in others—while still others suffer no apparent consequences. The condition varies enormously by individual. Additional symptomsHyperacusis is often accompanied by other symptoms. These include

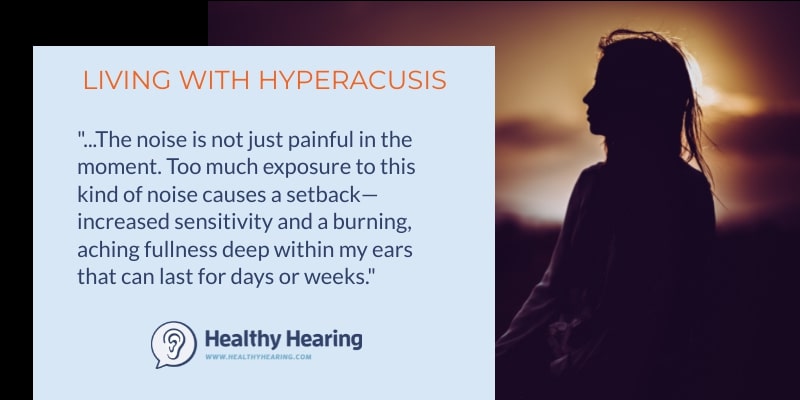

SetbacksWith time and quiet, hyperacusis often slowly improves on its own. People generally report substantial improvement within two years. But improvement is often deceptive, since the condition also worsens readily. The biggest danger is setbacks that come from more noise—even from moderate noises or those that don’t seem especially loud: a laugh, a bark, a honk. A car ride. A lively conversation.

People may feel they have fully recovered—but just one episode of noise exposure, like a favorite song turned up loudly—wipes out all their progress. A survey from Hyperacusis Research showed that escalating pain, increased tinnitus and lower noise tolerance from a setback can last for hours, days, weeks, or permanently. A full 56% of patients said their worst setback “made my condition worse than ever” while only 6% said their worst setback had “a small impact.” Another survey showed that 36% indicated they had a setback at least weekly. “Most learn from painful experiences that a key to progress is to minimize setbacks,” Pollard wrote. DiagnosisHyperacusis is generally a self-diagnosis, as is tinnitus. Audiologists typically deal with hearing loss, and are unlikely to be familiar with hyperacusis. Nor are doctors, though some informed medical practitioners can formulate a diagnosis by asking the right questions. The one test sometimes used for diagnosis is called a loudness discomfort level test (LDL), where beeps of different frequencies grow increasingly loud and patients identify the point when the noise becomes uncomfortable. The test, however, puts harsh noises into a delicate ear, which can cause a setback. So patients should know the risk of such a test.

Treatment and managementThe most important thing is to avoid more noise exposure, which can can cause further damage and delay healing. Some people with mild cases have found relief with sound therapy, using soft broadband background noise that is gradually — over months — raised in volume. Online information often goes into fine technical detail about white noise vs pink noise, though the bigger considerations is to find a comfortable noise. Some cases, however, worsen with sound therapy. Some patients find soft brown noise in the background to be particularly soothing, and such steady background noise can blunt the impact of a sudden jarring noise, like the shutting of a door. Another option is hyperacusis-focused desensitization therapy. Others try pain drugs or muscle relaxants, but the drugs carry side effects. Ear protection is vitalProtective equipment is essential for managing noise exposure. Many hyperacusis patients have an arsenal always at hand: Earplugs (which must be worn properly), noise-cancelling headphones (which work against steady low pitches, like throbbing vehicles) and protective earmuffs (generally more user-friendly than earplugs). One myth in the field is that “overprotection” worsens people. That advice originated from studies of healthy college students who wore earplugs 23-7 for two weeks and showed a very small and temporary decrease—just a handful of decibels—in their threshold of pain. This information has, unfortunately, been translated into the harmful advice that quiet makes hyperacusis worse, and has been circulated extensively around the web. In fact, noise is what aggravates hyperacusis, whereas quiet promotes healing. “Clinical advice rarely comprehends setbacks or the risk of making the condition worse,” Pollard wrote, stressing that clinicians should not claim that ordinary, everyday noise is perfectly safe. Once someone has hyperacusis, it isn’t. A day in the life of a person with hyperacusis

Author Joyce Cohen acquired hyperacusis, or noise-induced pain, after an acoustic trauma 15 years ago. She lives in New York City with her husband. Here's what a typical day with hyperacusis is like for her, showing how ordinary sounds are not just painful, but can make her hyperacusis worse. Joyce CohenJoyce Cohen, a newspaper reporter and magazine writer, writes primarily about health, noise and real estate. She wrote the first mainstream newspaper pieces about hyperacusis, misophonia and the danger of not just noise volume but duration, and covered restaurant noise as an emerging disability rights issue. She acquired hyperacusis after a noise injury. Joyce lives with her husband in New York. |

Featured clinics near me

Earzlink Hearing Care - Reynoldsburg

7668 Slate Ridge Blvd

Reynoldsburg, OH 43068

Find a clinic

Need a hearing test but not sure which clinic to choose?

Call 1-877-872-7165 for help setting up a hearing test appointment.